Thursday

Morning Read

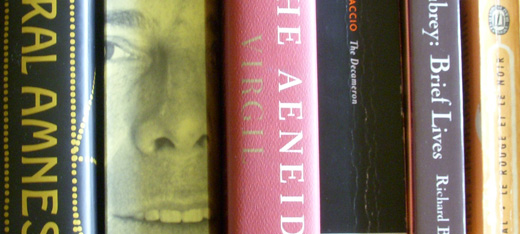

¶ In the Decameron, X, iii, the story of Nathan and Mithridanes, is the one that I would urge everyone to read, not so much because it’s a “good story” as because it casts a beautiful light on bygone mores. Again, as in X, i, the longing for recognition is praised as a sign of noble character, even though — this time — the fame-seeker seeks to murder the gentleman whose reputation he would outshine.

¶ In Aubrey, the last of the P’s: Popham, Potter, Prynne, and Pugh. Francis Potter (1594-1678) appears to be an interesting, but ultimately unlucky, transitional figure in the history of modern mechanics: most of his inventions were surpassed before or soon after his death. Here is the profile of your Seventeenth-Century geek:

He was always much contemplative, and had an excellent philosophical head. He was no greatly read man; he had a competent knowledge in the Latin, Greek and Hebrew tongues, but not a critical. Greek he learned by Montanus’ Interlineary Testament, after he was a man, without a grammar, and then he read Homer. He understood only common arithmetic, and never went farther in geometry than the first six books of Euclid; but he had such an inventive head, that with this foundation he was able to do great matters in the mechanics, and to solve phenomena in natural philosophy. He had but few books, which when he died were sold for 56 shillings, and surely no great bargain. he published nothing but his Interpretation of the number 666, printed at Oxford in 1642, which has been twice translated into Latin, into French, and other languages. He made that fine sun-deal, with its furniture, on the north wall of the quadrangle at Trinity College, which he did by Samminitatus’s book of sun-dialling (it has been gone since about 1670, and another in there put.)

¶ James Merrill on “Alabaster”

Thanks to it, for centuries a glow

Not quite of this world lit

Sanctum, princeling, folio.

Always too late

We saw the stricken cow, the rabble below

With catapult and crossbow.

Now came the age of glass.

Each room boasted a device whereby

Misbehavior, even miles away,

Could be perceived. (Uh-oh.

From then on it was curtains, both for us

And for the window.)

Visible meanwhile, we had to clean

Our act up. Probity, good sense?

Zero to 1 on the Mohs scale — yet, we’d learn,

Indistinguishable on a wide screen

From marble, rosy with concern:

The stuff of Presidents.

¶ Clive James on Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, a Nazi collaborator who gassed himself (how fitting) in 1945. By chance, I saw a movie about South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission yesterday, and I’m heartened by the improvement, since the end of World War II, in the civilized manner of closing the wounds of civil war. Of France after the War, James writes,

It was a time for fake virtue: a time in which there was no sure sign of real virtue except diffidence. … A good moral test for the business is that while Camus saw that there had to be a reckoning but thought it should be done regretfully, Sartre was an untroubled enthusiast.