Thursday

Morning Read

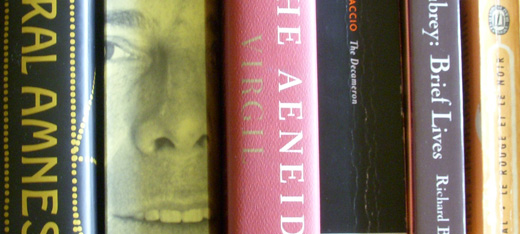

¶ In the Decameron, we come to the end of the Eighth Day, with the tale of Salabaetto, the gulled Florentine, and Jancofiore, the scheming Sicilian. Dioneo sexes up his tale with some very gratuitous lewdness involving slave girls and bathtubs, but in the end the wicked lady rues her misjudgment: Chi ha a far con tosco, non vuole esser losco, which McWilliam renders nicely as “Honesty’s the better line, when dealing with a Florentine.” (Note: tell Édouard about the Tuscan’s name.)

¶ In the Aeneid, a passage for Ms Clinton to consider —

multa dies variique labor mutabilis aevi

rettulit in melius, multos alterna revisens

lusit et in solido rursus Fortuna locavit.

Many things

the run of the days and shifting works of fickle time

have turned from bad to good. Many men has two-faced

Fortune cheated, only to come back and set them up

on solid ground once more.

— bearing in mind how things worked out for the speaker, Turnus.

¶ In Aubrey, the life of Hobbes, nearly fifteen pages of miscellaneous trivia. Of Hobbes’s acquaintance with Galileo, Aubrey notes that the two men “had both a consimility of fate, to be hated and persecuted by ecclesiastics.” He assumes that we know why — and I suppose we do. Sounding rather like my father (who said of me that I had more books than sense), Hobbes “was wont to say that if he had read as much as other men, he should have known no more than other men.”

¶ In Le rouge et le noir, the marquis settles some property on Julien, and even finds him a place in the Hussars — but he can’t bring himself to permit Mathilde to marry the young man. More dithering: but I believe that things will pick up in the next chapter. Big time.

¶ Clive James on Paul Celan, the Rumanian poet who took his own life at the age of fifty, and who therefore was arguably not a survivor of the Holocaust. Noting that Celan is best-known for “Todesfuge,” a poem of very uncharacteristic accessibility, James takes a pot shot at George Steiner for admiring Celan’s more impenetrable verse. Along the way, James offers one of those gems of good advice that are too rarely of any use:

There are no simplistic rules for poets: if there were, any duffer could write poetry. There are, however, rules of thumb, and one of the best is that getting the focus off yourself gives you the best chance of tapping your personal experience.

This is the sort of thing that we learn from experience when we finally have some. Youth experiences only itself, which is not experience at all.