Thursday

Morning Read

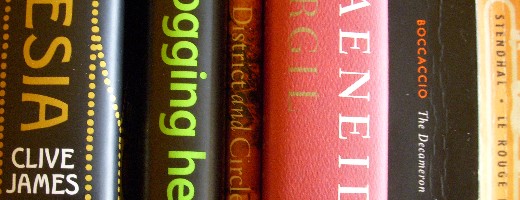

¶ Someone ought to publish a slim paperback edition of the Day Six of the Decameron — for the use of after-dinner speakers.

In VI, iv, a cook has to explain away his having cut off a succulent morsel of roast crane — one of its legs, to be exact — in order to retain the favors of a kitchen wench. He tells his complaining master that cranes have only one leg, as indeed they appear to do when they sleep. When the master, outraged, bellows at a flock of cranes the next morning, scaring the birds into flight (and into showing both legs), the cook has the wit to chide him for having failed to shout “Boo” at the roast. All is forgiven.

¶ In the Aeneid, more pastoral touches that combine the grand and the humble in Poussin’s trademark style.

Talibus inter se dictis ad tecta subibant

pauperis Euandri, passimque armenta videbant

Romanoque Foro et lautis mugire Carinis.

ut ventem ad sedes, “haec,” inquit, “limina victor

Alcides subiit, haec illum regia cepit.

aude, hospes, contemnere opes et te quoque dignum

finge deo, rebusque veni no asper egenis.”So,

conversing and drawing near Evander’s humble home,

they saw herds of cattle, everywhere, lowing loud

in the Roman Forum and Carinae’s elegant district.

“These gates,” Evander says, as he reaches his lodge,

“Hercules in his triumph stooped to enter here.

This mansion of mine was grand enough for him.

Courage, my friend! Dare to scoff at riches.

Make yourself — you too — worthy to be a god.

Come into my meager house, and don’t be harsh.”

Actually, what this really reminds me of is Bellini’s St Francis, at the Frick.

¶ In Le rouge et le noir, romance heats up between Julien and Mathilde. It is, of course, a romance of mutual dislike, a sort of Nineteenth-Century screwball. I don’t think that we’re going to wind up laughing, though.

L’amour-propre de Julian était flatté. Une personne environnéee de tant de respects, et qui, au dir de l’académicien, menait toute la maison, daignait lui parler d’un air qui pouvait presque ressembler à de l’amitié.

Je m’étais trompé, pensa bientôt Julien: ce n’est pas de la familiarité, je ne sui qu’un confident de tragédie, c’est le besoin de parler. Je passe pour savant dans cette famille. Je m’en vais lire Brantôme, d’Aubigné, l’Étoile. Je pourrai contester quelques-unes des anecdotes dont me parle mademoiselle de La Mole. Je veux sortir de ce rôle de confident passif.

It is so like Julien to imagine that Mathilde sees him as the “companion in a tragedy” to her starring role.

¶ Anyone who has read this far in Cultural Amnesia knows what to expect from Clive James on the subject of Trotsky.

Trotsky’s undoubted fluency as a polemical journalist does not mean that he wouldn’t rather have had a gun in his hand. The humanist makes a big mistake in supposing that a literary talent automatically ameliorates the aggressive instinct. Osama bin Laden has several of Trotsky’s characteristics…

When I was a callow teenager, hearing about Trotsky & Co for the first time from the lips of critically admiring young men slightly older than myself, I despaired of ever becoming an intellectual, because I could work up exactly no enthusiasm for chaotic social upsets. I was so ashamed of myself in this regard that it took me forever to see the truth of James’s acid truth: “Trotsky’s idea of permanent revolution will always be attractive to the kind of romantic who believes that he is being oppressed by global capitalism when he maxes out his credit card.”