Monday

Morning Read

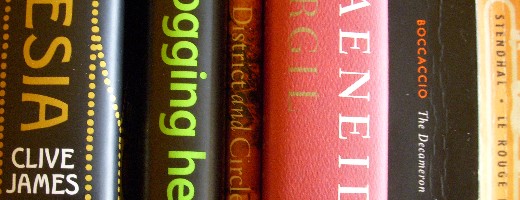

Monday Housekeeping Note: With only two chapters of Blogging Heroes left, I’ll be revising the reading list this week. The new titles will be John Aubrey’s Brief Lives and Wallace Stevens’s Harmonium.

Coming up: the Aeneid will be followed by Simon Armitage’s new translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Edith Grossman’s new translation of Don Quixote will follow the Decameron. These changes are weeks, if not months, away, so you’ve plenty of time, if you’re interested in following along, to arm yourself with either book.

On the horizon: James Merrill, Michel de Montaigne, Richard Burton, and the correspondence of George Sand and Gustave Flaubert.

¶ The tales of the Decameron’s Sixth Day are extremely brief, as if to echo those of the First. The theme of the Day is quite as twisted in Italian as it is in English.

…the discussion turns upon those who, on being provoked by some verbal pleasantry, have returned like for like, or who, by a prompt retort or shrewd manoeuvre, have avoided anger, discomfort or ridicule.

The first tale is quite literally over before it begins. Any déjà vu that the reader might feel at the start is perfectly warranted, for the language almost exactly repeats the opening of I, x. A lady interrupts a knight who, although he has chosen a good story to tell her, cannot tell it well. “Sir, you have taken me riding on a horse that trots very jerkily. Pray be good enough to set me down.” The knight takes this is good humor, which is truly fabulous.

Before Filomena can begin, however, an altercation in the kitchens intrudes on the lords and ladies. The disagreement, between a cook and a valet, is decidedly unseemly: was the wife of one Sicofante a virgin when she married or not? Licisca, the cook, stoutly claims that the woman was far too sensible to have “squandered her opportunities” while waiting for matrimony. Tindaro naively disagrees. That the gentlefolk should take it upon themselves to arbitrate the question is about as fanciful as anything in the Decameron, but it must have served as a combination amuse-gueule and dirty postcard to refresh the reader who had made it this far.

¶ In the Aeneid, the Arcadian Evander, newly settled in Italy, receives Aeneas and pledges an alliance — once it has been worked out that both men are descendants of Atlas. Evander politely remembers a childhood encounter with Aeneas father, and specifies the gifts that Anchises bestowed upon him at the time: a quivery, a cape, and a pair of “gilded reins.” I wish I knew the literary term for Evander’s courtly two-step here; I’m sure that something highly artificial is going on, something intended to tickle the connoisseurs among Virgil’s first readers.

¶ Chapter VII of Book II of Le rouge et le noir reads like a memo to self, Stendhal’s notes for the chapter. M de La Mole suffers a prolonged attack of gout and, having no one else to talk to, makes a pet of Julien. Is the novelist still paying attention at this point? Julien is sent off on a junket to London, where he has a handful of adventures that seem rather coded. Stendhal seems to take no interest in explaining Julien’s encounters, but he does toss off a few epigrams. “Secundo, L’esprit et le génie perdent vingt-cinq pour cent de leur valeur en débarquant en Angleterre.” He praises the English countryside, though.

¶ Clive James on Tacitus — whom he claims to be the inspiration of Cultural Amnesia. First, James takes Tacitus to task for not “getting” the iniquity of slavery. Then he forgives him, because what Tacitus did get was priceless: the horror of unlimited power, which can render lawful the most criminal behavior. The essay wraps up somewhat cloudily; I transcribe it to witness my own inadequacy as a reader.

Great writing collapses time by freeing us from illusions, one of which is that the aesthetic impulse can be a law unto itself. An advantage of being able to write criticism in the wonderfully copious English language is that we are not stuck with an inappropriate word to register the impact of art at its height. Hearing the voice of Sejanus’s daughter, we are not obliged to say, “That’s beautiful.” In Italian, even the mighty Croce could only have used the word bello. Croce painted himself into a corner with an aesthetic vocabulary that he inherited but fatally neglected to expand. The warning is clear. An aesthetic vocabulary is only part of what we need. Criticism needs a complete vocabulary, or else the rare art that responds to the whole of reality will leave us helpless; and far from being able to appreciate Tacitus, we won’t even be able to appreciate Hermann Graebe.

My attention snags on James’s not telling us what Croce might have said in English.

¶ Today’s Blogging Hero: Victor Agreda, of DIY Life, the third of this book’s thirty sites that I can imagine visiting with genuine curiosity. (The other two are PostSecret and Luxist.) But instead of talking about the blog, the chapter focuses on the career history that has lead Mr Agreda to his berth at Weblogs, Inc. An unexpected air of dissatisfaction and frustration lingers in the Q&A.

You’ve got things like Digg that have just truly accelerated the rate at which news spreads. There’s a no hiding it. And it’s very difficult to compete against the hive mind of the thousands of bloggers out there, online all the time.

I have two kids at home, and I can’t stay on the computer all day and all night. So I can’t compete against some 15-year-old who’s stuck in his house all day through the summer.

In short, it’s difficult for us to break news. It’s difficult for us to contribute something that has not already been discovered.

I’m worn out just reading it. Fortunately, there’s hope. From the Power Points:

Blogging for free on your own may win the attention of paying blogs.

Will the person who needed to be told that bit of news please stand up? You car is illegally parked in the middle of Times Square, with the lights on, the doors locked, and your keys in the ignition.