Morning Read:

Plunder

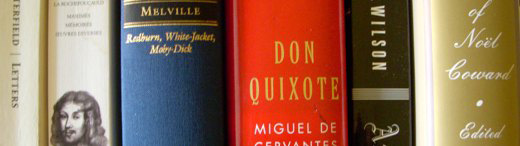

This morning’s Read bored me quite to sobs. Lord Chesterfield’s letter, which I’ll get to in a moment, was the only good thing — but I’d read it before. Don Quixote and Sancho had a particularly silly and pointless quarrel that might have amused me if I had not been laid low by an excruciating chapter in Moby-Dick (the one about the history of the Enderbys and the Coffins — I can’t be bothered to touch the book twice in one day) and a lot of context-free chitchat in Squillions — than which it is impossible to imagine a worse-edited collection of letters. It might help if I understood — really understood — what Herman Melville and Barry Day set out to accomplish. All that I see is tedious inappropriateness.

Writing about the difficulty of determining the mainspring of a man’s character, Chesterfield seizes on the examples provided by those two eminent cardinals, Richelieu and Mazarin — though he goes at them in reverse order.

I mean ambition and avarice: the latter is often the true cause of the former, and then is the predominant passion. It seems to have been so in Cardinal Mazarin, who did anything, submitted to anything, and forgave anything, for the sake of plunder. He loved and courted power, like an usurer, because it carried profit along with it. Whoever should have formed his opinion or taken his measure singly, from the ambitious part of Cardinal Mazarin’s character, would have found himself often mistaken. Some who had found this out, made their fortunes by letting him cheat them at play. On the contrary, Cardinal Richelieu’s prevailing passion seems to have been ambition, and his immense riches only the natural consequences of that ambition gratified; and yet I make no doubt but that the ambition had now and then its turn with the former, and avarice with the latter. Richelieu (by the way) is so strong a proof of the inconsistency of human nature, that I cannot help observring to you, that while he absolutely governed both his King and his country, and was, in a great degree, the arbiter of the fate of all Europe, he was more jealous of Corneille than of the power of Spain; and more flattered with being thought (what he was not) the best poet, than with being thought (which he certainly was) the greatest statesman in Europe; and affairs stood still while he was concerting his criticism upon the Cid.

For my part, I don’t see Richelieu’s literary ambition as an inconsistency.

The cadence “did anything, submitted to anything, and forgave anything, for the sake of plunder” is magnificently dishy. “Plunder” is exactly the mot juste. It sounds like dirty laundry.